Saturday, August 6, 2016

By Phillip Weyhe

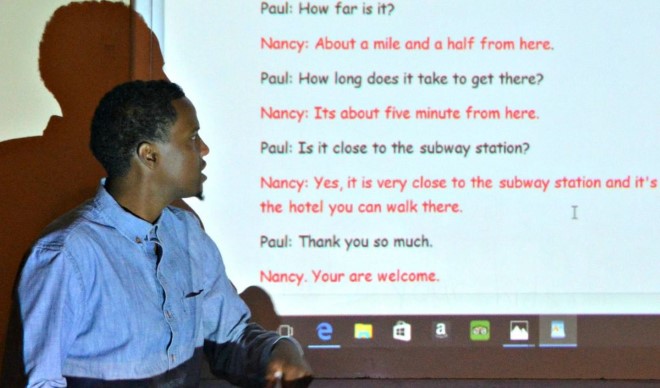

Ibrahim Khalif goes over some basic English with adults learning the language at the Fairbault Diversity Coalition. Khalif, born in Somalia and raised in Kenya, had to learn the language himslef before graduating from Fairbault High School and Central College. (Phillip Weyhe/ Daily News)

A decade after leaving Kenya, Somali-born Faribault resident Ibrahim Khalif feels “more Minnesota than Africa.”

The 25-year-old Faribault High School and South Central College graduate has established a life for himself in his new country. And in the city where he made it all happen, he’s giving back.

“I believe everybody is friendly,” he said. “You just have to be out there showing it. If you want to do positive, it begins with you.”

Khalif currently works at Faribault Diversity Coalition, where he helps new immigrant and refugee families to learn English and adjust to American life in general. Any kind of assistance, from finding housing to finding a job to navigating the grocery store, is on the table at FDC.

He and some of the other teachers draw on their own experiences, transitioning to a new country, to connect with the students.

“We know their culture. We understand their needs,” said Abdi Abdullahi, an EL teacher at FDC and Faribault School District.

“These people are brand new. They get traumatized,” Khalif said. “They’re fresh off the boat basically. I’m just trying to help them start their life. We’ll help anybody. Anybody that needs help.”

Somalia-Kenya

Khalif was born in a small Somalian city in the early 1990s, during a period of great civil unrest within the country. His family chose to move to Kajiado in Kenya when he was very young to find safer pastures.

His father eventually moved to America on his own, in order to send money back home and allow the children to receive an education. He found a job at Jennie-O Turkey in Faribault and stayed for decades.

Khalif, meanwhile, spent his childhood mostly in schools. The schedule was grueling. From about 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., he attended regular elementary and secondary school. From 5 to 8 p.m., he attended madrasa, where he learned Arabic. Then from 8 to 10 p.m., he attended dugsi, where he learned the Quran.

“Then I’d go to sleep,” he said.

School was different in Kenya. Students were disciplined for showing up late, teachers had all the power and kids knew to be quiet in class.

“There’s a teacher with a stick if you do something wrong, or they’ll make you go dig a hole with a shovel,” Khalif said. “If you show up late after lunch, they’d make you run a couple miles around the school.”

Khalif doesn’t speak of his old schools in a negative tone. It was just a “different environment.”

Perhaps his fondest memories of childhood, though, were of the weekends. With no school obligations, he and his neighborhood friends got together to play soccer and volleyball on the dry Kenyan soil, barefoot and joyful.

They’d also go to a nearby lake, about half the size of Cannon Lake in Faribault, to swim on the hottest days. Now and then, they’d have to chase off some snakes with rocks, sticks and whatever else they could find.

“We were just a bunch of kids,” Khalif said.

Faribault

In 2005, when Khalif was about 15, his father managed to attain visas for the family to join him in Faribault. Khalif had visions of what life in American would be.

“I was expecting big buildings and mansions out there. What you see in Hollywood. My American dream was everything was big and everything is extra fancy,” he said. “I realized you have to work for it. It’s out there, but you have to go get it.”

So he worked hard. He knew basic English but little more. Thrown into a new education system as a freshman at FHS, he was lost at the start.

In classes, he saw students talking and ignoring teachers with no punishment in return. To him, this meant students must not respect the teachers, as that kind of student freedom was not the norm at his schools in Kenya.

“Everything was just different. It was like the teachers were too nice. It seemed like the students have more control,” he said.

Despite the unfamiliar surroundings, the culture gap, the language barrier, Khalif pushed on. He was determined to catch up in school, and his time in Kenya taught him how to work hard for an education.

“It’s all about dedication,” he said. “You have to push yourself. Nobody else is going to do that for you.”

He managed to graduate on time in 2009. Before graduating, he had started working at Kentucky Fried Chicken. He used money generated from that to help pay for college at SCC, continuing to work there while attending school through 2011.

Once again, he reached graduation and suddenly the world was a little more open.

“I have more freedom. I can become who I want,” he said. “The sky is the limit.”

Currently at FDC, Khalif is helping to show other immigrants and refugees what the United States can do for them. It’s a lot, noted fellow teacher Abdullahi.

“They get better education, better security, better health, better infrastructure, social amenities,” he said. “Families are supported. This country has done marvelous things for all of us.”

Khalif, himself, has a few options going forward. His associate’s degree from South Central College is in liberal arts, and he also received a certificate in phlebotomy. He is looking at an opportunity at a plasma center in the Twin Cities and is considering continuing college to become a Medical Laboratory Technician.

Whatever he does, wherever he goes, he’ll be involved.

“I was taught to every day become a better person than yesterday,” he said. “I learned that growing up. Always serve your community, no matter the outcome.”