Wednesday March 13, 2024

by Becky Z. Dernbach

Superintendent Lisa Sayles-Adams apologized to parents Tuesday over the cuts outlined last week at a district finance committee meeting.

Muna Garad, seen Tuesday, March 12, 2024, at a Minneapolis school board meeting, said she transferred her daughter from a charter school to Lyndale Elementary when she heard about the district's Somali heritage language program. Credit: Aaron Nesheim | Sahan Journal

A week after the Minneapolis Public Schools proposed extensive cuts to its heritage language programs, and told several staff members their jobs would be eliminated, the district has reversed course.

The move came after pushback from Somali and Hmong parents and teachers, including vows by some to leave the district.

Superintendent Lisa Sayles-Adams announced the reversal at Tuesday night’s school board meeting and apologized for the confusion.

“No reductions to the central office facilitator positions that support the Somali and Hmong language pathways, or the biliteracy seals, will be included in our budget,” Sayles-Adams said at the beginning of the meeting.

Given the history, the nature of the programs, and already limited resources for the programs, Sayles-Adams said, the heritage language cuts “should not have been an option.”

“I am very sorry for the confusion and distress the community has experienced over the past week,” she said.

The reversal comes after two separate petitions from parents and university professors, pushback from parents at a district finance committee meeting, a meeting between the Somali heritage language coordinator and the superintendent, and inquiries from Sahan Journal.

Deqa Muhidin, who coordinates Somali heritage language programs for Minneapolis Public Schools—and who was slated to lose her job—described the superintendent’s response as “beyond my wildest dreams.”

“In less than a week, our parents were able to advocate for their kids’ heritage language learning,” she said. “Our parents were able to advocate for multilingual leaders. And the district was surprisingly able to receive the message and respond appropriately.”

She said Sayles-Adams appeared to be a “listening leader” and hoped that this was a sign that the new superintendent, who started her job in February, would incorporate feedback from families in her decision-making.

The Minneapolis Public Schools unveiled its Somali heritage language program in fall 2021. Now in its third year, it has grown to serve 350 students in kindergarten through third grade; the district also offers Somali language classes at two high schools. The district also has a similar, older program aimed at Hmong students. In select schools, teachers pull interested students out of class to practice Somali through reading, math, or science lessons. Parents have reported that their children are often more comfortable in English than Somali, and worry that younger generations will lose their language skills, as well as a connection to culture and their community.

The budget whiplash over the heritage language programs confused teachers who were cut and then reinstated, as well as several parents who spoke with Sahan Journal who believed the programs would be eliminated altogether. Those parents told Sahan Journal that even if only the program leadership was cut, they believed those cuts would lead to the program’s ultimate disintegration.

Deqa credited the parents’ quick mobilization for the district’s turnaround.

”We started this program because we knew long-term how that would impact student lives,” she said. “We knew that parents would be supportive, and parents asked for it. And to see it become a movement of its own is very, very surreal.”

A preview of district-wide cuts

The pushback to heritage language cuts began the night that district staff gave the first overview of next year’s budget. Minneapolis Public Schools officials have said they are facing an overall budget deficit of at least $110 million, largely due to the expiration of federal COVID funds in September. In a school board finance committee meeting March 5, district staff unveiled a preview of the extensive cuts the district will face across nearly every school. The full proposed budget for next school year has not yet been made available to the public, or even to the school board. The budget will not be finalized until the school board votes on it in June.

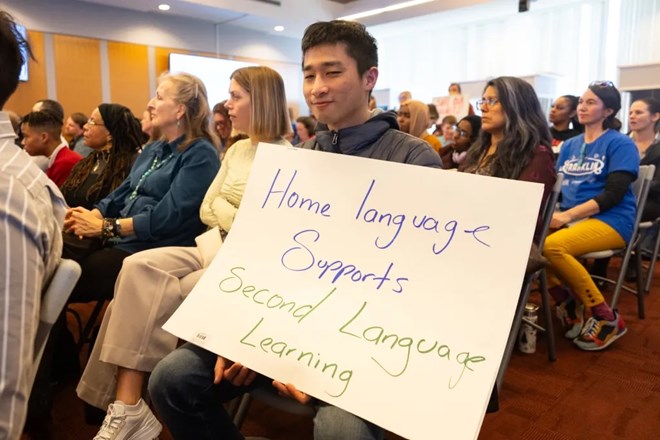

Two dozen Somali and Hmong parents attended the March 5 meeting, holding signs with phrases like “Multilingual students a priority,” “Preserve heritage languages,” and “Raising proud Somali speakers.”

At that meeting, finance committee chair Abdul Abdi asked Aimee Fearing, the senior officer of academics, about any proposed cuts to Somali and Hmong heritage language programs.

Fearing clarified that the Hmong and Somali heritage language programs would not be eliminated. However, she said, the district proposed reducing the number of heritage language teachers from seven to five. And all district office staff that support the heritage language programs would be eliminated.

“Completely?” Abdul asked.

“Completely,” Fearing confirmed.

Jeffery Ting, of the Coalition of Asian American Leaders, attends a Minneapolis School Board meeting to show support for the district’s Heritage Language Program on March 12, 2024. Credit: Aaron Nesheim | Sahan Journal

The full proposed budget has not been made available, and Minneapolis Public Schools did not confirm which staff members would be affected by the proposed cuts. But district office staff for the heritage language programs include one coordinator each for the Hmong program and the Somali program, as well as a staff member who coordinates the district’s biliteracy seals. This program allows bilingual students to earn college credit from a language proficiency test.

Among the proposed cuts was Deqa, who had played a key role in creating the Somali heritage program, coordinating the curriculum, and successfully pushing for a legislative change to allow educators to earn a license in teaching heritage languages.

Abdul asked Fearing who would support heritage teachers obtaining licenses, and reminded her that the central office staff had written the law that made those licenses even possible.

The passage of that bill was “one of the most joyous moments in my time here,” Fearing replied, and acknowledged that Deqa had played a major role in creating the law.

“There’s a lot of hard decisions we’re making,” Fearing said, “a lot of impact to our staff here at Davis, and I care really deeply about that.”

‘Language is the compass for the kids’

One of the teachers affected by the cuts, as Fearing described them on March 5, was Adam Bulale, a Somali heritage language teacher at Sullivan STEAM School. Adam started his position in December as Sullivan’s second Somali heritage language teacher; he estimates more than 60% of students there are Somali.

But many of them are more comfortable speaking English than Somali, he said. Some students don’t know any Somali words when they first come to his class; then after three or four weeks, they start reading in the language.

“Language is the compass for the kids,” Adam said. “When you don’t have language or culture, you’re going to be a lost person.”

Adam said he had first learned of the cuts from his principal, who had told him the district planned to fund only one Somali teacher next year. But three days later, he said, his principal told him the district had changed its mind. An email obtained by Sahan Journal shows that on March 7, Fearing told staff she had reallocated funds to preserve his position as well as a Hmong heritage language position at Olson Middle School.

Even so, Adam did not feel clear about his job status for next year. As he understood the conversation with his principal, he would be laid off at the end of the year and then rehired—which did not make him confident he would have a job next year. He was currently looking for other jobs, he said Monday.

‘Taking the heart out of the body’

Though Adam and his counterpart at Olson Middle School were reinstated, program leaders still thought they were out of a job until Tuesday.

Hurio Jama and Muna Garad, mothers of children in the Somali heritage program at Lyndale Elementary School, told Sahan Journal on Tuesday afternoon that they would leave the district if cuts to the program went forward.

Muna sent her daughter to kindergarten at Hennepin Elementary School, a charter school. She found it to be a good cultural fit for her family. But her daughter came to Lyndale for first grade when Muna heard about the new Somali language program. Her daughter, who had barely been able to speak Somali, quickly learned to read whole sentences and sing in the language.

“Even if it was in Owatonna, I would drive my kid,” Muna said of the heritage language program.

Hurio said that she had grown up in the United States and did not know every Somali word.

“Half of the time I feel like I don’t fit into my own community,” she said. “I don’t want my kiddo going through that.”

Muna and Hurio questioned how the district expected the program to function without a leader.

“We feel like they’re taking the heart out of the body, but they want the limbs to function,” Muna said.

Deqa Muhidin, the district program facilitator for Somali heritage language in Minneapolis Public Schools, and Alex Vitrella, program director for the nonprofit Education Evolving, celebrated a new law that would make it easier for heritage language teachers for languages like Somali, Hmong, and Karen to get a teaching license at the Minnesota Capitol in May 2023. Credit: Jaida Grey Eagle | Sahan Journal 2023

Deqa had provided traditional clothing and other materials for a heritage language event last summer, Hurio said. She knew that Deqa had also supplied curriculum and Somali books for her kids’ teacher, Farhiya Del.

Without Deqa, Hurio said, “How will Miss Farhiya function, and do her job?”

Removing the program’s leadership would show that the district intended to gut the program over time, Hurio said.

“I feel like next year, there’s going to be another reason to get rid of the whole program in general,” she said.

Mission accomplished

The boardroom was at capacity when the meeting began, which meant that Muna was shut out of Sayles-Adams’ announcement. During a meeting pause to allow Muslims observing Ramadan to break their fast, Sahan Journal filled her in on what the superintendent had said. Muna grinned.

“We are ecstatic!” Muna said. “Mission accomplished!”

Her exit plan to leave the district was canceled, she said. “I will gladly stay.”

Hurio, too, said she was “glad everything worked out,” and said she would stay in the district.

Deqa reflected on the power parents had exerted.

“Our parents showed up for their kids,” Deqa said. She noted that this kind of engagement is often difficult for immigrant parents because of work and life commitments. “To have this many parents come on the second day of Ramadan spoke volumes.”

She also appreciated the superintendent’s apology.

“To have leadership start the board meeting acknowledging the harm that was done was something I also did not expect,” she said. She said she hoped it was a sign of change.

A different approach in St. Paul

Minneapolis Public Schools is not the only district facing major budget cuts. According to a survey by the Association of Metropolitan School Districts, 70% of metro area districts are facing shortfalls. That includes a projected budget shortfall of $107 million in St. Paul Public Schools.

St. Paul Public Schools has not yet outlined its plans for making budget cuts. In a February 27 news conference, however, Superintendent Joe Gothard outlined some items that he did not plan to cut. Among his top priorities to protect from cuts: culturally affirming schools. Earlier this year the St. Paul district credited these schools for helping to stabilize enrollment after years of decline. Among those programs is a Hmong heritage language program from prekindergarten through 12th grade.

“The charge from the community is many of our students and families leave because they don’t feel seen, heard, and valued in St. Paul Public Schools,” Gothard said. “And that hits my heart as an educator, as someone who cares about the children.”

He described how the St. Paul district opened its new East African Elementary Magnet School in just three months last year; the year before, it opened a new middle school for Hmong language and culture as a companion to the longstanding elementary school. The district has also said it plans to expand its high school offerings for Karen and Somali language classes, and explore culturally affirming offerings for African American students.

“This is what our community is asking for,” Gothard said.